Novena to Pope St. Pius X

Glorious Pontiff, Saint Pius the X, devoted servant of Our Lord and loving child of Mary, I invoke you as a saint in Heaven. I give myself to you that you may always be my father, my protector and my guide in the way of holiness and salvation. Aid me in observing the duties of my state in life. Obtain for me great purity of heart and a fervent love of the interior life after your own example.

Pope of the Blessed Sacrament, teach me to love Holy Mass and Holy Communion as the source of all grace and holiness and to receive this Sacrament as often as I can.

Gentle father of the poor, help me to imitate your charity toward my fellowmen in word and deed. Consoler of the suffering, help me to bear my daily cross patiently and with perfect resignation to the will of God. Loving Shepherd of the flock of Christ obtain for me the grace of being a true child of Holy Mother Church.

Saint Pius the X beloved Holy Father, I humbly implore your powerful intercession in obtaining from the Divine Heart of Jesus all the graces necessary for my spiritual and temporal welfare. I recommend to you in particular this favor . . . . (mention your request)

Great Pontiff, whom Holy Mother Church has raised to the honor of our altars and urged me to invoke and imitate as a Saint, I have great confidence in your prayers. I earnestly trust that if it is God's Holy Will, my petition will be granted through your intercession for me at the throne of God. St. Pius the X pray for me and for those I love. I beg of you, by your love for Jesus and Mary, do not abandon us in our needs. May we experience the peace and joy of your holy death. Amen

Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory be, three times each

____________________________________

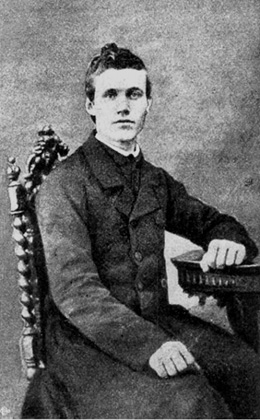

Pope St. Pius X

from the Roman Breviary

Pope Pius X, whose name previously was Joseph Sarto, was born in the village of Riese in the Venetian province, to humble parents remarkable for their godliness and piety. He enrolled among the students in the seminary of Padua, where he exhibited such piety and learning that he was both an example to his fellow students and the admiration of his teachers. Upon his ordination to the priesthood, he laboured for several years first as curate in the town of Tombolo, then as pastor at Salzano. He applied himself to his duties with such a constant flow of charity and such priestly zeal, and was so distinguished by the holiness of his life, that the Bishop of Treviso appointed him as a canon of the cathedral church and and made him the chancellor of the bishop's curia, as well as spiritual director of the diocesan seminary. His performance in these duties was so outstanding and so highly impressed Leo XIII, that he made him bishop of the Church of Mantua.

Lacking in nothing that maketh a good pastor, he laboured particularly to teach young men called to the priesthood, as well as fostering the growth of devout associations and the beauty and dignity of divine worship. He would ever affirm and promote the laws upon which Christian civilisation depend, and while leading himself a life of poverty, never missed the opportunity to alleviate the burden of poverty in others. Because of his great merits, he was made a cardinal and created Patriarch of Venice. After the death of Pope Leo XIII, when the votes of the College of Cardinals began to increase in his favour, he tried in vain with supplications and tears to be relieved of so heavy a burden. Finally he ceded to their persuasions, saying I accept the cross. Thus he accepted the crown of the supreme pontificate as a cross, offering himself to God, with a resigned but stedfast spirit.

Placed upon the chair of Peter, he gave up nothing of his former way of life. He shone especially in humility, simplicity and poverty, so that he was able to write in his last testament: I was born in poverty, I lived in poverty, and I wish to die in poverty. His humility, however, nourished his soul with strength, when it concerned the glory of God, the liberty of Holy Church, and the salvation of souls. A man of passionate temperament and of firm purpose, he ruled the Church firmly as it entered into the twentieth century, and adorned it with brilliant teachings. He restored the sacred music to its pristine glory and dignity; he established Rome as the principal centre for the study of the Holy Bible; he ordered the reform of the Roman Curia with great wisdom; he restored the laws concerning the faithful for the instruction of the catechism; he introduced the custom of more frequent and even daily reception of the Holy Eucharist, as well as permitting its reception by children as soon as they reach the age of reason; he zealously promoted the growth of Catholic action; he provided for the sound education of clerics and increased the number of seminaries in their divers regions; he encouraged every priest in the practice of the interior life; he brought the laws of the Church together into one body; he condemned and suppressed those most pernicious errors known collectively as Modernism; he suppressed the custom of civil veto at the election of a Supreme Pontiff. Finally worn out with his labours and overcome with grief at the European war which had just begun, he went to his heavenly reward on the twentieth day of August in the year 1914. Renowned throughout all the world for the fame of his holiness and miracles, Pope Pius XII, with the approbation of the whole world, numbered him among the Saints.

____________________________________

Prayers and Devotions of St. Pius X.

Ejaculation at the Elevation of the Mass and

at the Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament

Dominus meus, et Deus meus!

My Lord and my God!

(These words are to be said with faith, piety, and love, while looking upon the Blessed Sacrament, either during the Elevation in the Mass, or when exposed on the altar. Indulgence of 7 years. --Pius X, 1907.)

Come, O holy Ghost, fill the hearts of thy faithful, and kindle in them the fire of thy love.

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X. 1907.)

O Lord, preserve to us the Faith

(100 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1908.)

Jesus, meek and humble of heart, make my heart like unto Thine.

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1905.)

Sacred Heart of Jesus I trust in Thee.

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1906.)

Sacred Heart of Jesus, Thy Kingdom come!

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1906.)

Divine Heart of Jesus, convert sinners, save the dying, set free the Holy Soul in Purgatory.

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X)

Eternal Father, by the most Precious blood of Jesus Christ, glorify His most Holy Name, according to the intention and the desires of His Adorable Heart.

(300 Days. Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1908.)

Jesus and Mary, (invoked with the heart, if not with the lips).

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X. 1904.)

Let us, with Mary Immaculate, adore, thank, pray to and console the most Sacred and well-beloved Eucharistic Heart of Jesus.

(200 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1904.)

O Mary, bless this house, where thy name is ever held in benediction. All glory to Mary ever Immaculate, ever Virgin, blessed among women, the Mother of our Lord Jesus Christ, queen of Paradise.

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1905.)

____________________________

Prayer to St. Joseph by Pope St. Pius X

O glorious St. Joseph, model of all those who are devoted to labor, obtain for me the grace to work conscientiously, putting the call of duty above my natural inclinations, to work with gratitude and joy, in a spirit of penance for the remission of my sins, considering it an honor to employ and develop by means of labor the gifts received from God, to work with order, peace, moderation and patience, without ever shrinking from weariness and difficulties, to work above all with purity of intention and detachment from self, having always death before my eyes and the account that I must render of time lost, of talents wasted, of good omitted, of vain complacency in success, so fatal to the work of God. All for Jesus, all through Mary, all after thine example, O Patriarch, St. Joseph. Such shall be my watchword in life and in death. Amen.

From the 1910 Roman Breviary

Prayer to be said at the Beginning of Mass

Eternal Father, I unite myself with the intentions and affections of our Lady of Sorrows on Calvary, and I offer Thee the sacrifice which thy beloved Son Jesus made of Himself on the Cross, and now renews on this holy altar: First. To adore Thee and give Thee the honour which is due to Thee, confessing Thy supreme dominion overall things, and the absolute dependence of everything upon Thee, Thou Who art our one and last end. Second. To thank Thee for innumerable benefits received. Third. To appease Thy justice, irritated against us by so many sins, and to make satisfaction for them. Fourth. To implore grace and mercy for myself, for...., for all afflicted and sorrowing, for poor sinners, for all the world, and for the Holy Souls in Purgatory.

(300 Days Indulgence. St. Pius X, 1904.)

Prayer to Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament

O Virgin Mary, our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament, glory of the Christian people, joy of the universal Church, salvation of the world; pray for us, and awaken in all the faithful devotion to the Holy Eucharist in order that they may render themselves worthy to receive It daily.

(300 Days Indulgence. Pius X, 1907. )

____________________________

Prayer for the Conversion of Sinners

O Lord Jesus, most merciful Savior of the world, we beg and beseech Thee, through Thy most Sacred Heart, that all wandering sheep may now return to Thee, the Shepherd and Bishop of their souls. Who livest and reignest with God the Father and the Holy Spirit, God forever and ever. Amen.

(300 Days Pius X, 1905.)

"An obligation of charity," says Pius X, "rests on rich men and holders of property to help the poor and needy according to the Gospel precept; and so grave is this precept that on the day of Judgment, according to Christ Himself, a special reckoning will be made of its fulfillment."

Lamentabili Sane, July 3, 1907

Syllabus Condemning the Errors of the Modernists

With truly lamentable results, our age, casting aside all

restraint in its search for the ultimate causes of things, frequently

pursues novelties so ardently that it rejects the legacy

of the human race. Thus it falls into very serious errors, which

are even more serious when they concern sacred authority,

the interpretation of Sacred Scripture, and the principal

mysteries of Faith. The fact that many Catholic writers also

go beyond the limits determined by the Fathers and the

Church herself is extremely regrettable. In the name of higher

knowledge and historical research (they say), they are looking

for that progress of dogmas which is, in reality, nothing but

the corruption of dogmas.

These errors are being daily spread among the faithful. Lest

they captivate the faithfuls' minds and corrupt the purity of

their faith. His Holiness, Pius X, by Divine Providence, Pope,

has decided that the chief errors should be noted and condemned

by the Office of this Holy Roman and Universal

Inquisition.

Therefore, after a very diligent investigation and consultation

with the Reverend Consultors, the Most Eminent and

Reverend Lord Cardinal, the General Inquisitors in matters of

faith and morals have judged the following propositions to be

condemned and proscribed. In fact, by this general decree,

they are condemned and proscribed.

1. The ecclesiastical law which prescribes that books concerning

the Divine Scriptures are subject to previous examination does

not apply to critical scholars and students of scientific exegesis of

the Old and New Testament. CONDEMNED

2. The Church's interpretation of the Sacred Books is by

no means to be rejected; nevertheless, it is subject to the more

accurate judgment and correction of the exegetes. CONDEMNED

3. From the ecclesiastical judgments and censures passed

against free and more scientific exegesis, one can conclude

that the Faith the Church proposes contradicts history and

that Catholic teaching cannot really be reconciled with the true

origins of the Christian religion. CONDEMNED

4. Even by dogmatic definitions the Church's magisterium

cannot determine the genuine sense of the Sacred Scriptures. CONDEMNED

5. Since the deposit of Faith contains only revealed truths,

the Church has no right to pass judgment on the assertions

of the human sciences. CONDEMNED

6. The "Church learning" and the "Church teaching"

collaborate in such a way in defining truths that it only remains

for the "Church teaching" to sanction the opinions of

the "Church learning." CONDEMNED

7. In proscribing errors, the Church cannot demand any

paternal assent from the faithful by which the judgments she

issues are to be embraced. CONDEMNED

8. They are free from all blame who treat lightly the

condemnations passed by the Sacred Congregation of the

Index or by the Roman Congregations. CONDEMNED

9. They display excessive simplicity or ignorance who

believe that God is really the author of the Sacred Scriptures. CONDEMNED

10. The inspiration of the books of the Old Testament

consists in this: The Israelite writers handed down religious

doctrines under a peculiar aspect which was either little or

not at all known to the Gentiles. CONDEMNED

11. Divine inspiration does not extend to all of Sacred

Scriptures so that it renders its parts, each and every one,

free from every error. CONDEMNED

12. If he wishes to apply himself usefully to Biblical studies,

the exegete must first put aside all preconceived opinions

about the supernatural origin of Sacred Scripture and interpret

it the same as any other merely human document. CONDEMNED

13. The Evangelists themselves, as well as the Christians

of the second and third generation, artificially arranged the

evangelical parables. In such a way they explained the scanty

fruit of the preaching of Christ among the Jews. CONDEMNED

14. In many narrations the Evangelists recorded, not so

much things that are true, as things which, even though false,

they judged to be more profitable for their readers. CONDEMNED

15. Until the time the canon was defined and constituted,

the Gospels were increased by additions and corrections.

Therefore there remained in them only a faint and uncertain

trace of the doctrine of Christ. CONDEMNED

16. The narrations of John are not properly history, but a

mystical contemplation of the Gospel. The discourses contained

in his Gospel are theological meditations, lacking historical

truth concerning the mystery of salvation. CONDEMNED

17. The fourth Gospel exaggerated miracles not only in

order that the extraordinary might stand out but also in order

that it might become more suitable for showing forth the work

and glory of the Word Incarnate. CONDEMNED

18. John claims for himself the quality of witness concerning

Christ. In reality, however, he is only a distinguished

witness of the Christian life, or of the life of Christ in the

Church at the close of the first century. CONDEMNED

19. Heterodox exegetes have expressed the true sense of the

Scriptures more faithfully than Catholic exegetes. CONDEMNED

20. Revelation could be nothing else than the consciousness

man acquired of his relation to God. CONDEMNED

21. Revelation, constituting the object of the Catholic faith,

was not completed with the Apostles. CONDEMNED

22. The dogmas the Church holds out as revealed are not

truths which have fallen from heaven. They are an interpretation

of religious facts which the human mind has acquired by

laborious effort. CONDEMNED

23. Opposition may, and actually does, exist between the

facts narrated in Sacred Scripture and the Church's dogmas

which rest on them. Thus the critic may reject as false facts

the Church holds as most certain. CONDEMNED

24. The exegete who constructs premises from which it

follows that dogmas are historically false or doubtful is not

to be reproved as long as he does not directly deny the dogmas

themselves. CONDEMNED

25. The assent of faith ultimately rests on a mass of

probabilities. CONDEMNED

26. The dogmas of the Faith are to be held only according

to their practical sense; that is to say, as preceptive norms of

conduct and not as norms of believing. CONDEMNED

27. The divinity of Jesus Christ is not proved from the

Gospels. It is a dogma which the Christian conscience has

derived from the notion of the Messias. CONDEMNED

28. While He was exercising His ministry, Jesus did not

speak with the object of teaching He was Messias, nor did His

miracles tend to prove it. CONDEMNED

29. It is permissible to grant that the Christ of history is

far inferior to the Christ Who is the object of faith. CONDEMNED

30. In all the evangelical texts the name "Son of God" is

equivalent only to that of "Messias." It does not in the least

way signify that Christ is the true and natural Son of God. CONDEMNED

31. The doctrine concerning Christ taught by Paul, John,

and the Councils of Nicaea, Ephesus and Chalcedon is not that

which Jesus taught but that which the Christian conscience

conceived concerning Jesus. CONDEMNED

32. It is impossible to reconcile the natural sense of the

Gospel texts with the sense taught by our theologians

concerning the conscience and the infallible knowledge of

Jesus Christ. CONDEMNED

33. Everyone who is not led by preconceived opinions can

readily see that either Jesus professed an error concerning

the immediate Messianic coming or the greater part of His

doctrine as contained in the Gospels is destitute of authenticity. CONDEMNED

34. The critics can ascribe to Christ a knowledge without

limits only on a hypothesis which cannot be historically

conceived and which is repugnant to the moral sense. That

hypothesis is that Christ as man possessed the knowledge of

God and yet was unwilling to communicate the knowledge

of a great many things to His disciples and posterity. CONDEMNED

35. Christ did not always possess the. consciousness of

His Messianic dignity. CONDEMNED

36. The Resurrection of the Saviour is not properly a fact

of the historical order. It is a fact of merely the supernatural

order (neither demonstrated nor demonstrable) which the

Christian conscience gradually derived from other facts. CONDEMNED

37. In the beginning, faith in the Resurrection of Christ

was not so much in the fact itself of the Resurrection as in

the immortal life of Christ with God. CONDEMNED

38. The doctrine of the expiatory death of Christ is Pauline

and not evangelical. CONDEMNED

39. The opinions concerning the origin of the Sacraments

which the Fathers of Trent held and which certainly influenced

their dogmatic canons are very different from

those which now rightly exist among historians who examine

Christianity. CONDEMNED

40. The Sacraments had their origin in the fact that the

Apostles and their successors, swayed and moved by circumstances

and events, interpreted some idea and intention of

Christ. CONDEMNED

41. The Sacraments are intended merely to recall to man's

mind the ever-beneficent presence of the Creator. CONDEMNED

42. The Christian community imposed the necessity of

Baptism, adopted it as a necessary rite, and added to it the

obligation of the Christian profession. CONDEMNED

43. The practice of administering Baptism to infants was

a disciplinary evolution, which became one of the causes why

the Sacrament was divided into two, namely. Baptism and

Penance. CONDEMNED

44. There is nothing to prove that the rite of the Sacrament

of Confirmation was employed by the Apostles. The

formal distinction of the two Sacraments of Baptism and

Confirmation does not pertain to the history of primitive

Christianity. CONDEMNED

45. Not everything which Paul narrates concerning the

institution of the Eucharist (I Cor. 11; 23-25) is, to be taken

historically. CONDEMNED

46. In the primitive Church the concept of the Christian

sinner reconciled by the authority of the Church did not

exist. Only very slowly did the Church accustom herself to

this concept. As a matter of fact, even after Penance was

recognized as an institution of the Church, it was not called

a Sacrament since it would be held as a disgraceful Sacrament. CONDEMNED

47. The words of the Lord, "Receive the Holy Spirit; whose

sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them; and whose sins

you shall retain, they are retained" (John 20: 22-23), in no

way refer to the Sacrament of Penance, in spite of what it

pleased the Fathers of Trent to say. CONDEMNED

48. In his Epistle (Ch. 5:14-15) James did not intend to

promulgate a Sacrament of Christ but only commend a pious

custom. If in this custom he happens to distinguish a means

of grace, it is not in that rigorous manner in which it was

taken by the theologians who laid down the notion and

number of the Sacraments. CONDEMNED

49. When the Christian supper gradually assumed the

nature of a liturgical action those who customarily presided

over the supper acquired the sacerdotal character. CONDEMNED

50. The elders who fulfilled the office of watching over the

gatherings of the faithful were instituted by the Apostles as

priests or bishops to provide for the necessary ordering of the

increasing communities and not properly for the perpetuation

of the Apostolic mission and power. CONDEMNED

51. It is impossible that Matrimony could have become a

Sacrament of the new law until later in the Church since it

was necessary that a full theological explication of the doctrine

of grace and the Sacraments should first take place

before Matrimony should be held as a Sacrament. CONDEMNED

52. It was far from the mind of Christ to found a Church

as a society which would continue on earth for a long course

of centuries. On the contrary, in the mind of Christ the

kingdom of heaven together with the end of the world was

about to come immediately. CONDEMNED

53. The organic constitution of the Church is not immutable.

Like human society, Christian society is subject to

a perpetual evolution. CONDEMNED

54. Dogmas, Sacraments and hierarchy, both their notion

and reality, are only interpretations and evolutions of the

Christian intelligence which have increased and perfected

by an external series of additions the little germ latent in

the Gospel. CONDEMNED

55. Simon Peter never even suspected that Christ entrusted

the primacy in the Church to him. CONDEMNED

56. The Roman Church became the head of all the

churches, not through the ordinance of Divine Providence,

but merely through political conditions. CONDEMNED

57. The Church has shown that she is hostile to the progress

of the natural and theological sciences. CONDEMNED

58. Truth is no more immutable than man himself, since

it evolved with him, in him, and through him. CONDEMNED

59. Christ did not teach a determined body of doctrine

applicable to all times and all men, but rather inaugurated a

religious movement adapted or to be adapted to different

times and places. CONDEMNED

60. Christian Doctrine was originally Judaic. Through

successive evolutions it became first Pauline, then Joannine,

finally Hellenic and universal. CONDEMNED

61. It may be said without paradox that there is no chapter

of Scripture, from the first of Genesis to the last of the

Apocalypse, which contains a doctrine absolutely identical

with that which the Church teaches on the same matter. For

the same reason, therefore, no chapter of Scripture has the

same sense for the critic and the theologian. CONDEMNED

62. The chief articles of the Apostles' Creed did not have

the same sense for the Christians of the first ages as they

have for the Christians of our time. CONDEMNED

63. The Church shows that she is incapable of effectively

maintaining evangelical ethics since she obstinately clings to

immutable doctrines which cannot be reconciled with modem

progress. CONDEMNED

64. Scientific progress demands that the concepts of Christian

doctrine concerning God, creation, revelation, the Person

of the Incarnate Word, and Redemption be readjusted. CONDEMNED

65. Modern Catholicism can be reconciled with true science

only if it is transformed into a non-dogmatic Christianity;

that is to say, into a broad and liberal Protestantism. CONDEMNED

The following Thursday, the fourth day of the same month

and year, all these matters were accurately reported to our

Most Holy Lord, Pope Pius X. His Holiness approved and

confirmed the decree of the Most Eminent Fathers and

ordered that each and every one of the above-listed propositions

be held by all as condemned and proscribed.

Peter Palombelli,

Notary of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition

On Rejecting Inovation and Protecting the Faith

"Our Apostolic Mandate requires from Us that We watch over the purity of the Faith and the integrity of Catholic discipline. It requires from Us that We protect the faithful from evil and error; especially so when evil and error are presented in dynamic language which, concealing vague notions and ambiguous expressions with emotional and high-sounding words, is likely to set ablaze the hearts of men in pursuit of ideals which, whilst attractive, are nonetheless nefarious."

Pope St. Pius X, Apostolic Letter Notre Charge Apostolique, 1910.

". . . . it is well known that to the Church there belongs no right whatsoever to innovate anything touching on the substance of the sacraments."

Pope St. Pius X, Ex quo, Dec. 26, 1910 as sourced from Denzinger. 2147 a

Oath Against Modernism

With the decree Lamentabili (1907) and the encyclical

Pascendi (1907), the dangers of the modernist interpretation of

Catholic truth had been exposed and fully expounded. Nevertheless,

efforts to promote the modernist cause were continued

in various countries. To eliminate the possibility of modernist

error spreading through the clergy, St. Pius X (1903-14) drew

up and published on September 1, 1910, the following oath

against modernism and imposed it on all clergy to be advanced

to major orders, on pastors, confessors, preachers, religious

superiors, and on professors in philosophical and theological

seminaries.

The first part of the oath is a strong affirmation of the basic

Catholic truths opposed to modernism: the demonstrability of

God's existence by human reason; the value and suitability of

miracles and prophecies as criteria of revelation; the historical

institution of the Church by Christ; the invariable character of

Catholic tradition; the reasonableness and supernaturalness

of faith.

The second part of the oath is an expression of interior assent

to the decree Lamentabili and the encyclical Pascendi with

their contents. Particular modernist errors are singled out for

censure and rejection.

I firmly embrace and accept each and every definition that has been set forth and declared by the unerring teaching authority of the Church, especially those principal truths which are directly opposed to the errors of this day.

And first of all, I profess that God, the origin and end of all things, can be known with certainty by the natural light of reason from the created world (see Rom. 1:20), that is, from the visible works of creation, as a cause from its effects, and that, therefore, his existence can also be demonstrated:

Secondly, I accept and acknowledge the external proofs of revelation, that is, divine acts and especially miracles and prophecies as the surest signs of the divine origin of the Christian religion and I hold that these same proofs are well adapted to the understanding of all eras and all men, even of this time.

Thirdly, I believe with equally firm faith that the Church, the guardian and teacher of the revealed word, was personally instituted by the real and historical Christ when he lived among us, and that the Church was built upon Peter, the prince of the apostolic hierarchy, and his successors for the duration of time.

Fourthly, I sincerely hold that the doctrine of faith was handed down to us from the apostles through the orthodox Fathers in exactly the same meaning and always in the same purport. Therefore, I entirely reject the heretical misrepresentation that dogmas evolve and change from one meaning to another different from the one which the Church held previously. I also condemn every error according to which, in place of the divine deposit which has been given to the spouse of Christ to be carefully guarded by her, there is put a philosophical figment or product of a human conscience that has gradually been developed by human effort and will continue to develop indefinitely.

Fifthly, I hold with certainty and sincerely confess that faith is not a blind sentiment of religion welling up from the depths of the subconscious under the impulse of the heart and the motion of a will trained to morality; but faith is a genuine assent of the intellect to truth received by hearing from an external source. By this assent, because of the authority of the supremely truthful God, we believe to be true that which has been revealed and attested to by a personal God, our Creator and Lord.

Furthermore, with due reverence, I submit and adhere with my whole heart to the condemnations, declarations, and all the prescripts contained in the encyclical Pascendi and in the decree Lamentabili, especially those concerning what is known as the history of dogmas. I also reject the error of those who say that the faith held by the Church can contradict history, and that Catholic dogmas, in the sense in which they are now understood, are irreconcilable with a more realistic view of the origins of the Christian religion. I also condemn and reject the opinion of those who say that a well-educated Christian assumes a dual personality--that of a believer and at the same time of a historian, as if it were permissible for a historian to hold things that contradict the faith of the believer, or to establish premises which, provided there be no direct denial of dogmas, would lead to the conclusion that dogmas are either false or doubtful. Likewise, I reject that method of judging and interpreting Sacred Scripture which, departing from the tradition of the Church, the analogy of faith, and the norms of the Apostolic See, embraces the misrepresentations of the rationalists and with no prudence or restraint adopts textual criticism as the one and supreme norm.

Furthermore, I reject the opinion of those who hold that a professor lecturing or writing on a historico-theological subject should first put aside any preconceived opinion about the supernatural origin of Catholic tradition or about the divine promise of help to preserve all revealed truth forever; and that they should then interpret the writings of each of the Fathers solely by scientific principles, excluding all sacred authority, and with the same liberty of judgment that is common in the investigation of all ordinary historical documents.

Finally, I declare that I am completely opposed to the error of the modernists who hold that there is nothing divine in sacred tradition; or what is far worse, say that there is, but in a pantheistic sense, with the result that there would remain nothing but this plain simple fact--one to be put on a par with the ordinary facts of history--the fact, namely, that a group of men by their own labor, skill, and talent have continued through subsequent ages a school begun by Christ and his apostles. I firmly hold, then, and shall hold to my dying breath the belief of the Fathers in the charism of truth, which certainly is, was, and always will be in the succession of the episcopacy from the apostles. The purpose of this is, then, not that dogma may be tailored according to what seems better and more suited to the culture of each age; rather, that the absolute and immutable truth preached by the apostles from the beginning may never be believed to be different, may never be understood in any other way.

I promise that I shall keep all these articles faithfully, entirely, and sincerely, and guard them inviolate, in no way deviating from them in teaching or in any way in word or in writing. Thus I promise, this I swear, so help me God.

The Life of Pius X:

The Life of Pius X:

Curate and Parish Priest

by Francis Alice Forbes, Imprimatur, 1918

The village of Tombolo, which lies in the province of Padua and the Diocese of Treviso, is surrounded by hilly and well-wooded country, watered by the tributary streams of the Brenta. The parish church, dedicated to St. Andrew, stands in the centre of the little township. Tombolo boasts of no commercial industries; it is a pastoral country, and the greater part of the population is occupied in dairy farming and the rearing of cattle. The people have clearly marked characteristics; strong and robust in build, hardened to sun, rain, and wind, rough-voiced and somewhat ungentle in manner, they have, nevertheless, good hearts and are in their own way religious.

But the Tombolani have one vice--or had when Don Giuseppe (future Pope St. Pius X) became their curate. They swore systematically and profusely at everything, at each other, and at the world at large. "No offence is intended to Almighty God," they explained ingenuously to the horrified young priest. "He certainly understands. Just go to market, and try to sell your beasts and your grain with a 'please' and a 'thank you,' and you will see what you will get!"

There may have been some truth in this; and intention, no doubt, goes a long way; but the argument did not satisfy Don Giuseppe. For the moment he dropped the subject, but he had not done with it.

The rector of the parish, Don Antonio Costantini, was habitually ailing. Devoted to his people and wholly desirous to do them good, his ill-health was a constant impediment. He had many tastes in common with his curate, notably the love of music and of biblical and patristic studies. He soon learnt to look upon Don Giuseppe as a son, and highly appreciated his good qualities.

"They have sent me a young man as curate," he wrote to a friend, "with orders to form him to the duties of a parish priest. I assure you it is likely to be the other way about. He is so zealous, so full of common sense and other precious gifts that I could find much to learn from him. Some day he will wear the mitre--of that I am certain--and afterwards? Who knows?"

The good rector nevertheless did his best to fulfil his commission. "Don Bepi," he would say to his young curate, "I did not quite like this or that in your last sermon." When the church was empty he would make Don Bepi go into the pulpit and preach, criticising and commenting the while both on matter and method; comments well worth having, for Don Antonio was a man of wide learning and an excellent theologian. Meanwhile Don Bepi, whose sermons were already becoming famous throughout the countryside for their zeal and eloquence, would listen humbly and promise to try to do better.

The income of the young curate was next to nothing, for Tombolo was a very poor parish; but he had not been used to luxury. He had planned his priestly life before his ordination, and was busy carrying out the scheme. To study deeply in order to fit himself more fully for preaching; to do as much good as was possible in the confessional and in the

pulpit; to help his people both materially and morally, to visit the sick, to succour the poor and to instruct the ignorant--such was the programme that he had traced out for himself, and with all the vigour of his soul he threw himself into the work.

The widowed niece of Don Antonio who kept house for her uncle used to see a light burning in the window of Don Giuseppe's poor lodging the last thing at night and the first thing in the morning.

"Do you never go to bed, Don Bepi?" she asked at breakfast one day, for the curate took his meals at the rectory.

Don Bepi laughed. "I study a good deal," he replied. He confessed later that he slept for four hours, and found it quite sufficient for his needs.

"He was as thin as a rake," said the good lady when pressed in after-life for reminiscences, "for he scarcely ate enough to keep body and soul together, and was never off his feet."

In the morning he would often ring the church bell for Mass, in order not to disturb the sacristan. Then he would go to fetch Don Antonio, having prepared for him all that was needed. Sometimes he would find his chief unwell and unable to rise.

"What is the matter?" he would ask in his cheery way--"another bad night?"

"I am afraid I cannot get up," would be the plaintive answer.

"Don't try to; stay quiet, and do not worry yourself. I will see to everything," the cheery voice would continue.

"But you have already one sermon to preach today, my Bepi."

"What of that? I will preach two." And so the conference would end.

During the days of sickness Don Giuseppe, as well as doing double duty, would constitute himself nurse to the poor invalid. How he managed it was known to himself alone.

He had not forgotten--there was no chance of forgetting--the deplorable language of his parishioners. The curate mixed with them as much as he could, making friends especially with the young men and the boys. He interested himself in their work and in their play, treating them with such a spirit of friendly comradeship that they would assemble in crowds to talk to him whenever he appeared. One day some of them lamented that they could neither read nor write.

"Let us start a night school," proposed Don Bepi, "and I will teach you."

"It would be too difficult," objected another; "some of us know a little, some less, and others nothing at all."

"What of that?" replied the priest. "We will have two classes--those who know something, and those who know nothing. We will get the schoolmaster to take the upper class, and I will teach the alphabet."

"Why shouldn't he teach the alphabet?" protested a loyal admirer of Don Giuseppe's.

Don Bepi laughed. "The alphabet is hard work," he answered, "I had rather keep it."

"But we can't take up your time like that for nothing," declared another. "What can we do for you in return?"

"Stop swearing," answered Don Bepi promptly, "and I shall then be more than repaid."

The school of singing made rapid progress in his hands. Don Antonio, who, like his curate, was an ardent lover of Gregorian music, warmly seconded all his efforts. The somewhat unmelodious, if extremely powerful, vocalisation of the village choir became soft and prayerful under his tuition. If one of the acolytes showed signs of a vocation to the priesthood, Don Giuseppe would teach him privately until he knew enough to go up for the examinations held at the diocesan seminary.

On one point Don Antonio and his curate could never agree. Everything that could be saved out of Don Giuseppe's miserable income went straight to the poor. They knew it; and when he went to preach in a neighbouring village, would lie in wait for him as he returned with his modest fee in his pocket. It sometimes happened that when he reached home not a penny would be left, and Don Antonio would think it his duty to remonstrate.

"It is not fair to your mother, Bepi," he would say; "you should think of her."

"God will provide for my mother," was the answer; "these poor souls were in greater need than she."

Invitations to preach in other parishes became more frequent, as the fame of the preacher increased. What he said was always simple, but it was full of teaching and went straight to the heart. The young priest had, moreover, a natural eloquence and a sonorous and beautiful voice. It was so evident that he spoke from the fulness of a soul on fire with the love of God that his enthusiasm was catching, and his sermons bore fruit.

It happened on one occasion that a priest who had been invited to preach on a certain feast-day in the neighbouring village of Galliera was prevented at the last moment from coming. There was consternation at the presbytery. What was to be dene?

"Leave it to me," said Don Carlo Carminati, curate of Galliera and a friend of Don Giuseppe; "I promise you it will be all right," and jumping into the presbytery pony-cart he took the road to Tombolo.

It was a Sunday afternoon in October and the hour of the children's Catechism class. Don Giuseppe was at the church door about to enter.

"Stop, stop," cried Don Carlo, "I want to speak to you." Don Giuseppe turned.

"You must come and preach at Galliera," said Don Carlo; "our preacher has fallen through."

"What are you thinking of?" exclaimed Don Giuseppe. "I cannot improvise in the pulpit!" and he turned once more to go into the church.

"You have got to come, your rector says so, and there is not a minute to lose," replied his friend; and, laying hold of the still expostulating Don Giuseppe, he packed him into the pony-cart, bowed to Don Antonio who stood smiling at the scene, and whipped up his steed.

Arrived at Galliera, Don Carlo conducted his victim to an empty room, provided him with pencil and paper and left him. An hour later, having been set at liberty by his triumphant fellow-curate, Don Giuseppe vested and entered the church.

The sermon that followed was so eloquent and so appropriate to the occasion that what had threatened to be a calamity became a cause for rejoicing.

"Did not I tell you?" exclaimed Don Carlo with pardonable exultation.

Don Giuseppe's energy was boundless, and to him no labour was degrading. "Work," he used to say, "is man's chief duty on earth." When the presbytery cook fell ill, he both nursed him and took his place; for in his eyes any kind of labour was a thing to draw men nearer to the Christ who was "Poor and in labours from His youth."

Whether it was preaching, teaching, playing with the village children to keep them out of mischief, visiting the sick, helping the dying, hearing confessions, catechising infants or studying theology, it was all the same to him--work for the Master, and as such ennobling and honourable.

So the time passed, until Don Giuseppe had been eight years at Tombolo. Much as Don Antonio loved and appreciated his curate, or rather because of this very love and appreciation, it distressed him to think that his talents should have no wider sphere than a little country parish. He spoke of this one day to one of the Canons of Treviso who was paying him a visit. The two curates of Galliera who were present joined enthusiastically in the praise of their friend. The Canon became thoughtful.

"Do you think he could preach in the Cathedral of Padua for the Feast of St. Anthony?" he asked after a moment of reflection.

"Most certainly, Monsignore," was the answer.

"Well," continued the Canon, "if you will be responsible for his accepting, I will see to it that he is asked."

The sermon was prepared, and the great day approached. The rector of Tombolo was more anxious than if he had been going to preach in the Duomo himself, for his interest in his beloved Bepi was that of a father, and he had formed great hopes for the future.

The feast-day sermon was naturally a topic of burning interest in Padua. "Who is to preach?" was the question on everybody's lips on the morning of the great day.

"Don Giuseppe Sarto, a young priest who is curate of Tombolo," was the reply.

Now it was customary on the Feast of St. Anthony to ask a preacher of some distinction to occupy the Cathedral pulpit.

"The curate of Tombolo!" was the apprehensive comment. "Oh dear! A country curate from an out-of-the-way village!"

The Cathedral was crowded for the High Mass celebrated in honour of Padua's patron saint. When the slight young figure of Don Giuseppe mounted the pulpit stairs there was a gasp of astonishment, which soon gave place to an expectant silence.

"His intelligence and culture were no less remarkable than his eloquence," wrote one of the congregation to a friend. "His imagery was beautiful, his style perfect." The sermon lasted over an hour, and no one thought it too long.

In the May of 1867 Don Giuseppe was appointed rector of Salzano. A wail of lamentation arose from the little parish where he had worked so faithfully for nearly ten years. "He was our father, our brother, our friend, and our comfort," cried the heartbroken Tombolani. In the heart of Don Antonio grief for his loss contended with joy at the thought that the merits of his beloved Don Bepi had been recognised at last.

Salzano is a small country town in the province of Venetia. It has a handsome church with a graceful campanile and a somewhat imposing presbytery. The country is fertile, and the people, who are wholly given to agriculture, are quiet, steady, and hardworking.

The new rector arrived on a Saturday evening in July. At Mass the next morning, in spite of the oppressive heat, the church was crowded, for the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages had assembled in force to hear the sermon of the newly appointed "Parroco."

The result was a delightful surprise. "What was the Bishop thinking of," they asked one another as they met when Mass was over, "to leave a man like that buried all these years at a place like Tombolo?"

As for Don Giuseppe, he set to work at once to visit his people. His frank simplicity, his understanding sympathy and zeal for their welfare gained their hearts at once. As at Tombolo, he gave special attention to the instruction of children; and, not content with this, inaugurated Catechism classes and classes of Christian doctrine for the adults of the parish.

"Most of the evil in the world," he would often say, "comes from a want of the knowledge of God and of His truth."

In spite of the large parish and the handsome rectory, Don Giuseppe's habits were as frugal as ever. There was more to give to the poor, that was all. His sister Rosina kept house for him.

"Bepi," she said one day, "there is nothing for dinner."

"Not even a couple of eggs?" asked the brother.

A couple of eggs there were, and on these they dined.

But there was always a welcome at the rectory and a share of anything that was going for any old friend who dropped in. Don Carlo came one evening for a visit, and found Don Giuseppe in the kitchen playing games with some little children of the parish. They were sent home with a promise that the game should be continued on another occasion, and Don Carlo was pressed to stay. The next morning he was accosted by Rosina.

"Don Carlo, you are an old friend, and a very kind one," she began hesitatingly, "there is a man coming to-morrow who sells shirting."

"Really?" answered Don Carlo, rather at a loss to connect the statements.

"Yesterday my brother got a little money," continued Rosina, "and he has hardly a shirt to his back. Now if you were to try to persuade him to buy some shirting, I think he perhaps would do it. Will you do your best?"

Don Carlo promised, and took the first opportunity of broaching the subject.

"Nonsense, nonsense," was the answer, "there is no necessity at all," and the plea was cut short in its infancy.

But Don Carlo was not so easily beaten, he knew the sunny nature of his friend, and determined to have recourse to strategy. On the arrival of the pedlar, he at once accosted him, examined his materials, selected what he considered suitable, and set to work, after the manner of his country, to bargain. Having agreed on what he considered a fair price, he ordered the required length to be cut off, and turning to Don Giuseppe who had been innocently watching the transaction. "So many yards at such and such a price," he declared. "Pay up, Don Giuseppe!"

The rector was disgusted; but there was nothing to be done but to obey. The bargain had been made and the shirting cut off. "Even you come here and plot to betray me," he complained.

As for Rosina, her delight knew no bounds. "God bless the day you came, Don Carlo," she said, meeting him outside the door. "If you had not been here today, tomorrow there would have been neither money nor linen!"

Salzano was a large parish, and the rector had to keep a conveyance. It was not much to look at, but it did hard service, being at the disposal of everybody who had recourse to the well-known charity of its owner. The horse came home one day with both knees broken.

"I am very sorry," pleaded the borrower, "an accident . . ."

Don Giuseppe swallowed down a very pardonable indignation. "Never mind, never mind," he said; "it is all right."

One day--there had been a bad harvest that year, and there was much poverty in the parish--the rector asked a friend who was in easy circumstances to sell the horse for him. "You have so many relations with money," he pleaded.

The horse having been disposed of, it was then suggested that the same friend might also sell the carriage.

"I don't think I shall succeed," he remarked doubtfully, "for you must allow that it is not in the best condition." His fears were too true; no purchaser was found, and the carriage remained in the presbytery stable at the disposal of anyone who possessed a horse without a vehicle.

In 1873 there was a serious outbreak of cholera. The people of Salzano knew little of hygiene and less of sanitation; it was hard to make them take the most necessary precautions. Don Giuseppe was everything at once: doctor, nurse, and sanitary inspector, as well as parish priest. Not only were there the sick and the dying to be tended, but the living to be heartened and consoled. "If it had not been for our dear Don Giuseppe," said an old man in later days, "I should have died of fear and sorrow during those dreadful trmes." Some of the people took it into their heads that the medicines and remedies ordered by the doctor were intended to put them quickly out of their pain, and would not take them unless they were administered by the priest's own hand.

For fear of infection, the dead had to be buried by night, and no one was allowed to attend the funeral. Anxious lest in the fear and the haste of the moment due honour should not be paid to these victims of the epidemic, Don Giuseppe was always there to see that all was done as it should be. Not only did he recite the prayers and carry out the ceremonies prescribed by the Church on such occasions, but would take his place as coffin bearer, and even helped to dig the graves. Sorrow at the heartrending scenes he had to witness, added to these incessant labours by night and by day, would have ruined a less robust constitution than his.

It is small wonder that Don Carlo Carminati, coming to visit him soon afterwards, was horrified at his appearance.

"You are ill?" he exclaimed.

"You think so?" was the quiet answer.

"He is ill," interposed Rosina vehemently, "but what can you expect? He is everybody's servant, he never spares himself. He has not only given away the food from his own mouth, but the night's rest which would have restored him. Look at him, nothing but skin and bone!"

"Your sister is right, you are doing too much. Remember that the pitcher can go to the well once too often; and when it is quite worn out, at a given moment it will break."

"You are becoming quite an eloquent orator," commented Don Giuseppe with a smile.

Don Carlo was a man of action. He wrote to Don Antonio Costantini telling him that their dear Don Giuseppe was killing himself, and begging him to give a hint to the diocesan authorities. The hint was duly conveyed and duly taken. The Bishop wrote to the rector of Salzano, ordering him to take a little more care of himself; but this was an art which Don Giuseppe had never studied, and he did not know how to begin. He continued to devote himself body and soul to his flock, leaving himself to the care of God. His strong constitution gradually recovered from the strain it had undergone, and the apprehensions of his friends were fortunately not realised.

With Don Giuseppe the service of Christ in His poor went hand in hand with the service of Christ on the altar. During his ministry at Salzano the parish church was greatly improved and beautified. He got together a voluntary choir of young men and boys and taught them himself to sing the stately Gregorian music that he loved for its devout and prayerful spirit. Even those who knew the stark poverty of the rector's private life did not always understand how the means could be obtained to carry out the plans he had at heart.

"But how will you get the money?" they would sometimes ask.

"God will provide," was the quiet answer, given with the serene faith characteristic of the strong.

http://catholicharboroffaithandmorals.com/

|